Gallery Facade. March 2020.

Sin Título, 2020, 55 x 69,5 cm, Etchings

Sin Título, 2020, 55 x 69,5 cm, Etchings

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Sin Título, 2020, 55 x 69,5 cm, Etching on paper; Sin Título, 2020, 55 x 69,5 cm, Etching on paper

Sin título, 2020, 226 x 270 cm, Graphite on paper mounted on wood board.

Sin título, 2020, 260 x 195 cm, Graphite on paper mounted on wood board.

Sin título, 2020, 226 x 270 cm, Graphite on paper mounted on wood board.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Sin título, 2020, 265 x 200 cm, Graphite on paper mounted on wood board.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

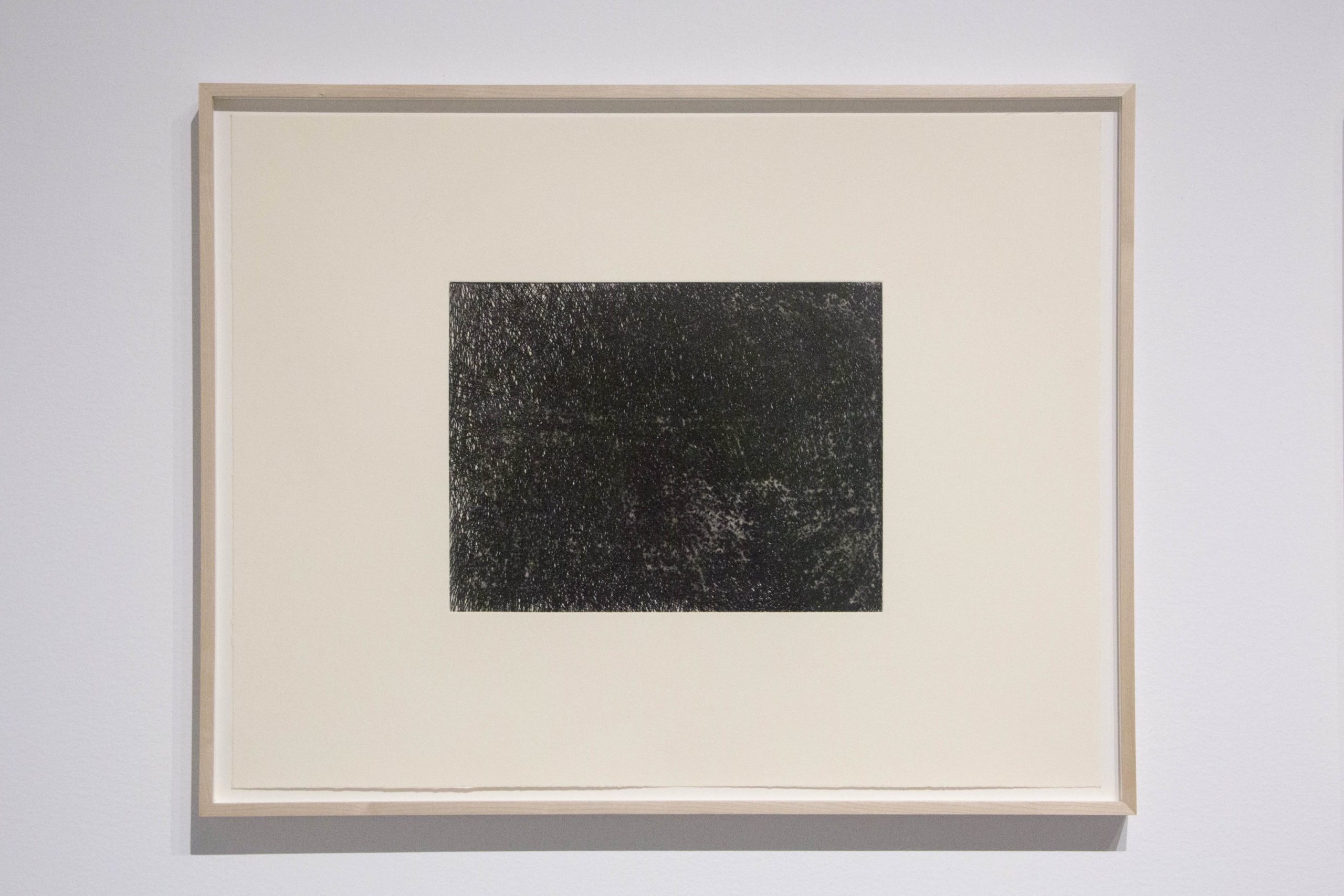

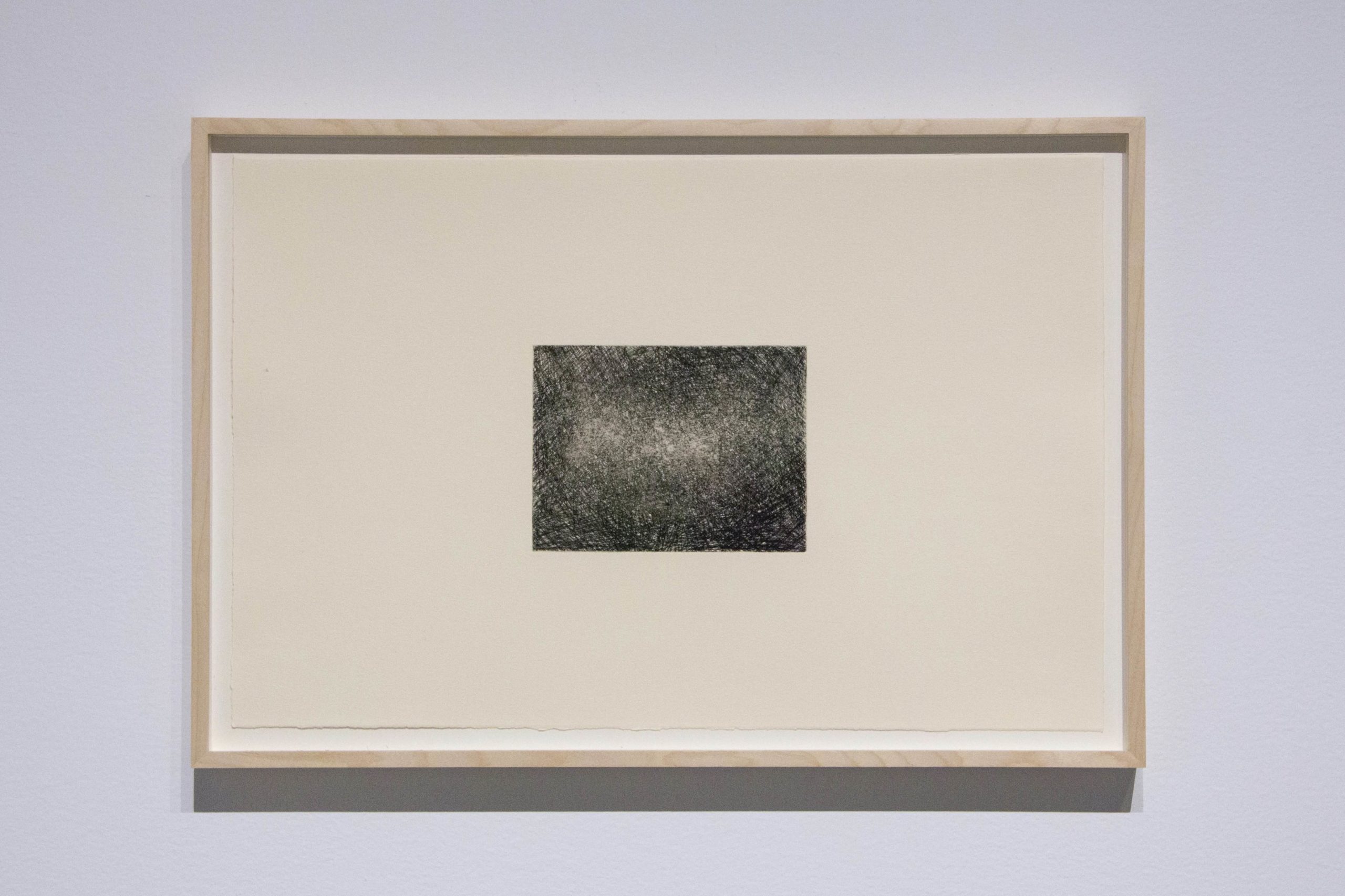

Sin título, 2020,39 x 56,5 cm, Etchings on paper, framed

Sin título, 2020,39 x 56,5 cm, Etchings on paper, framed .

Sin título, 2020,39 x 56,5 cm, Etchings on paper, framed .

Sin título, 2020,39 x 56,5 cm, Etchings on paper, framed

Sin título, 2020,39 x 56,5 cm, Etchings on paper, framed

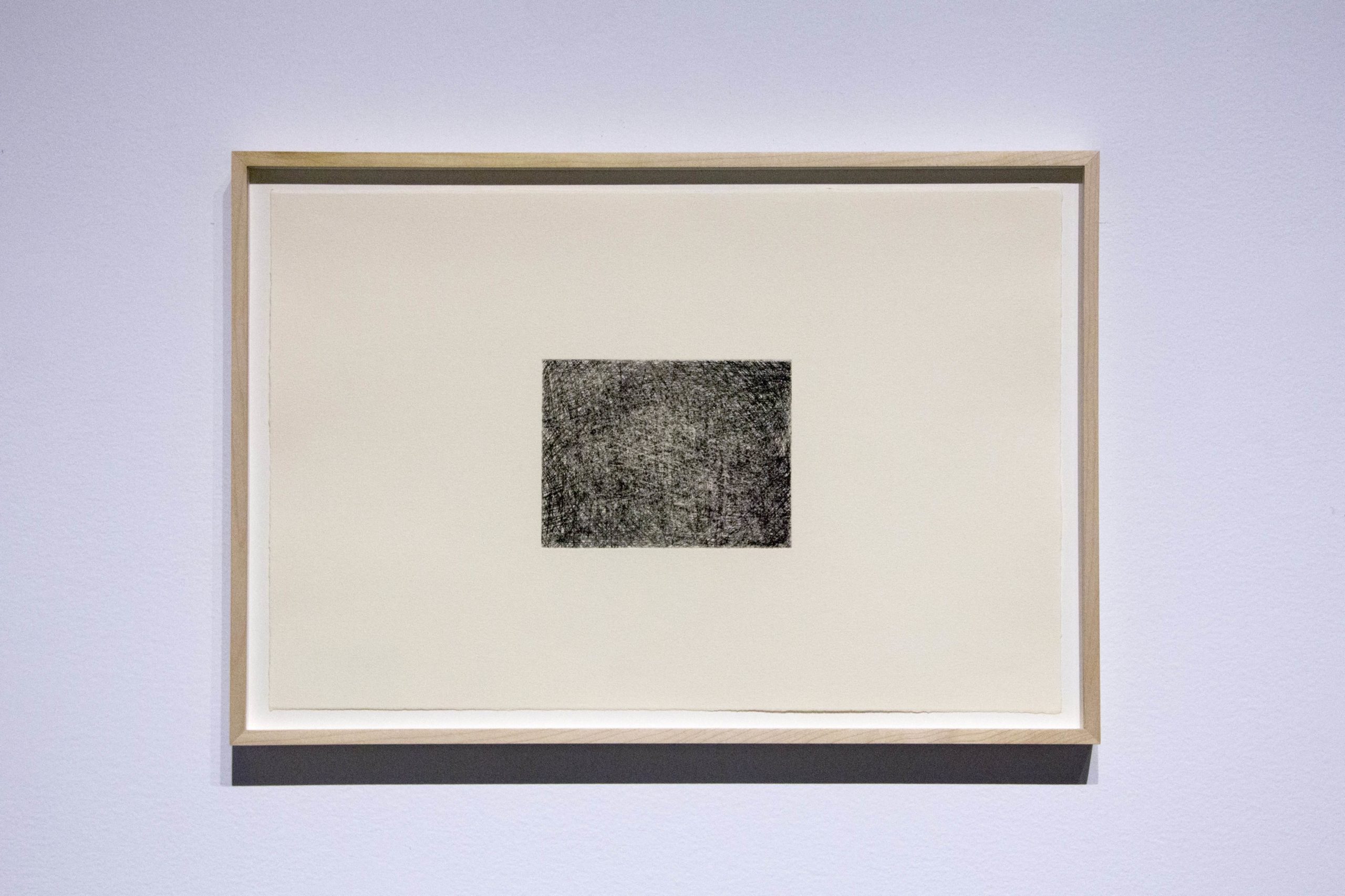

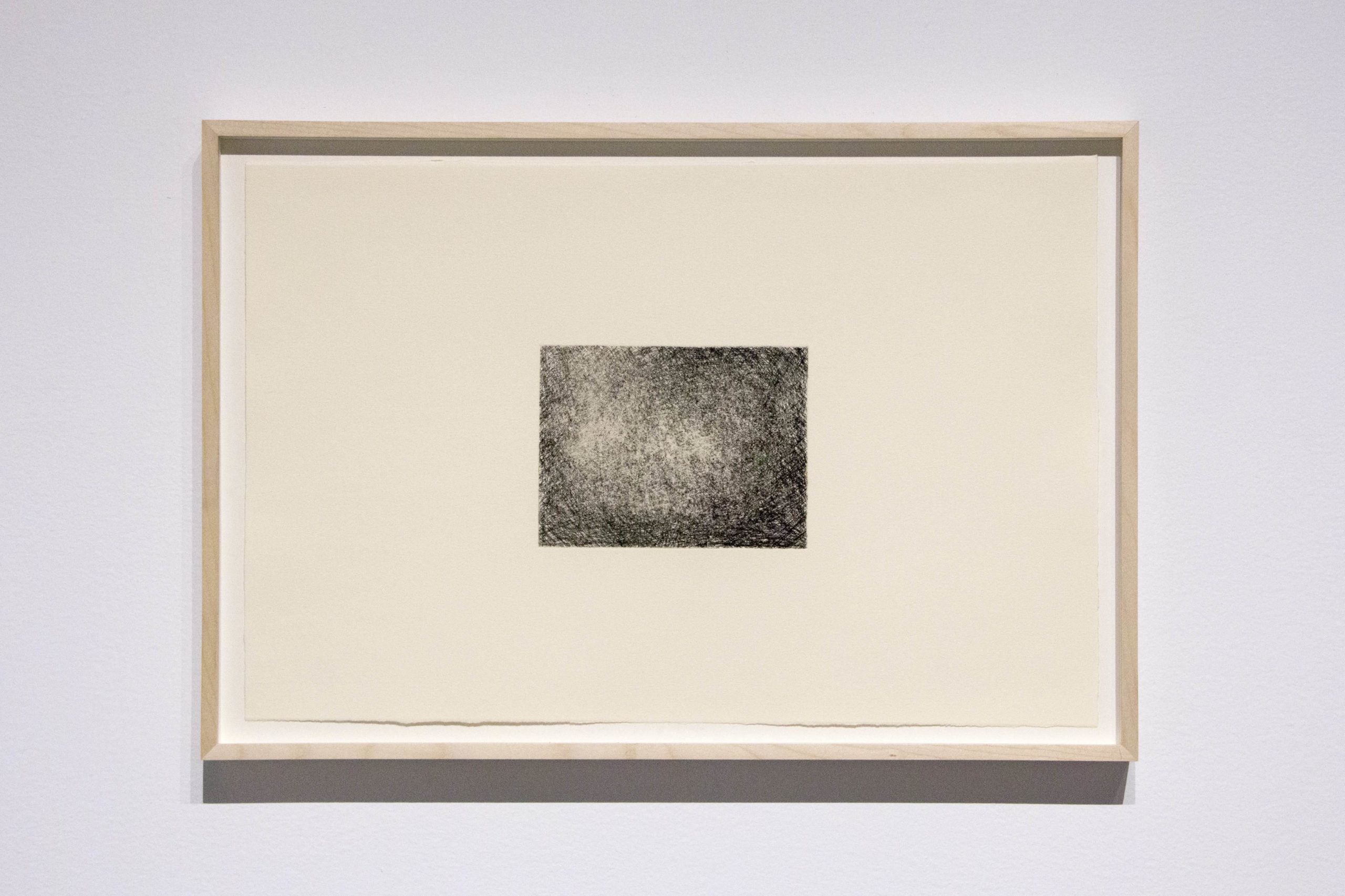

Sin título, 2020,34,5 x 48 cm, Etchings on paper, framed .

Sin título, 2020,34,5 x 48 cm, Etchings on paper, framed

Sin título, 2020,34,5 x 48 cm, Etchings on paper, framed

Information

“The captivating thing is not understanding where this manner of drawing comes from, discern-ingpossible influences or appreciating his ability to know when to cover the paper completely or stop atthe first line and deem it finished. What is perturbing is the reason that has led him to draw againtoday in a manner that seemed superseded, but which a little further thought shows to continuereferring us to an everyday world where marks on walls stilloffer us information, as they did whenBrassaïwandered the streets of Paris in search of graffiti: “Beauty is not the object of creation, it’s thereward. Its appearance, often tardy, announces simply that the broken balance between man andnature has once again been re-conquered by art. What remains of contemporary works after thisconfrontation?Nicolas Ortigosa’s drawing brings back a post́-war gesture closeto Hans Hartung’s obsessive trac-ing of lines, or Zoran Music’s ability to touch bottom in showing us that Goya’sWitches’ CovenorFeastof San Isidrocould also be Dachau. In a way, this type of gesture looks back to Paul Celan’swords after Auschwitz:“We dug a mass grave in the air, where there’s no straitness.” In all of them,and in every mark that is still made today directly on the wall or on a support destined for the wall,there is a dissident gesture on the basis of which a more or less controlled violence is exercised, onewhich occasionally survives usby centuries and becomes its witness. “All the walls of a city thatfamily tradition had persuaded me was utterly mine were witnesses to all the martyrdoms and all theinhuman underdevelopment inflicted on our people.”The way in which Nicolas Ortigosa intervenes on paper denotes an obsessive need to determine thélimits of the support itself, of the big bars of graphite, and of the space within his arms’ reach. Thecritic Michel Tapiéwas to say in 1952 that “the path of art appears to us as the path of contemplationappeared to St John of the Cross: steep and uneven, and stripped of any accessory satisfaction.”After Nietzsche and Dada, Tapiéasserted, art emerged as “the most inhuman of adventures.In Ortigosa’s practice, I sense a certain inclination for that introspection which keeps him isolat-ed,worried about nothing but whathappens within the walls of his studio. Interested perhaps in findinga closer link to the word, the result of his works suggests a poetic rapture that often seems elusiveand hard to explain. This is where I understand that surfing provides an activity inwhich organisationis para-mount: observation, waiting, decisions and action. In no case is the order of the factorschanged, and nev-er is it the man on the board who wins. The sea beats on as always, with itsrhythms and its rules.Ángel Calvo Ulloa, “Nicolás Ortigosa:working at the limits”, 2019.Exhibition catalogue“Nicolás Ortigosa.Works2002-2018”, Bombas Gens Centre d’Art, 2019