Gallery Façade.

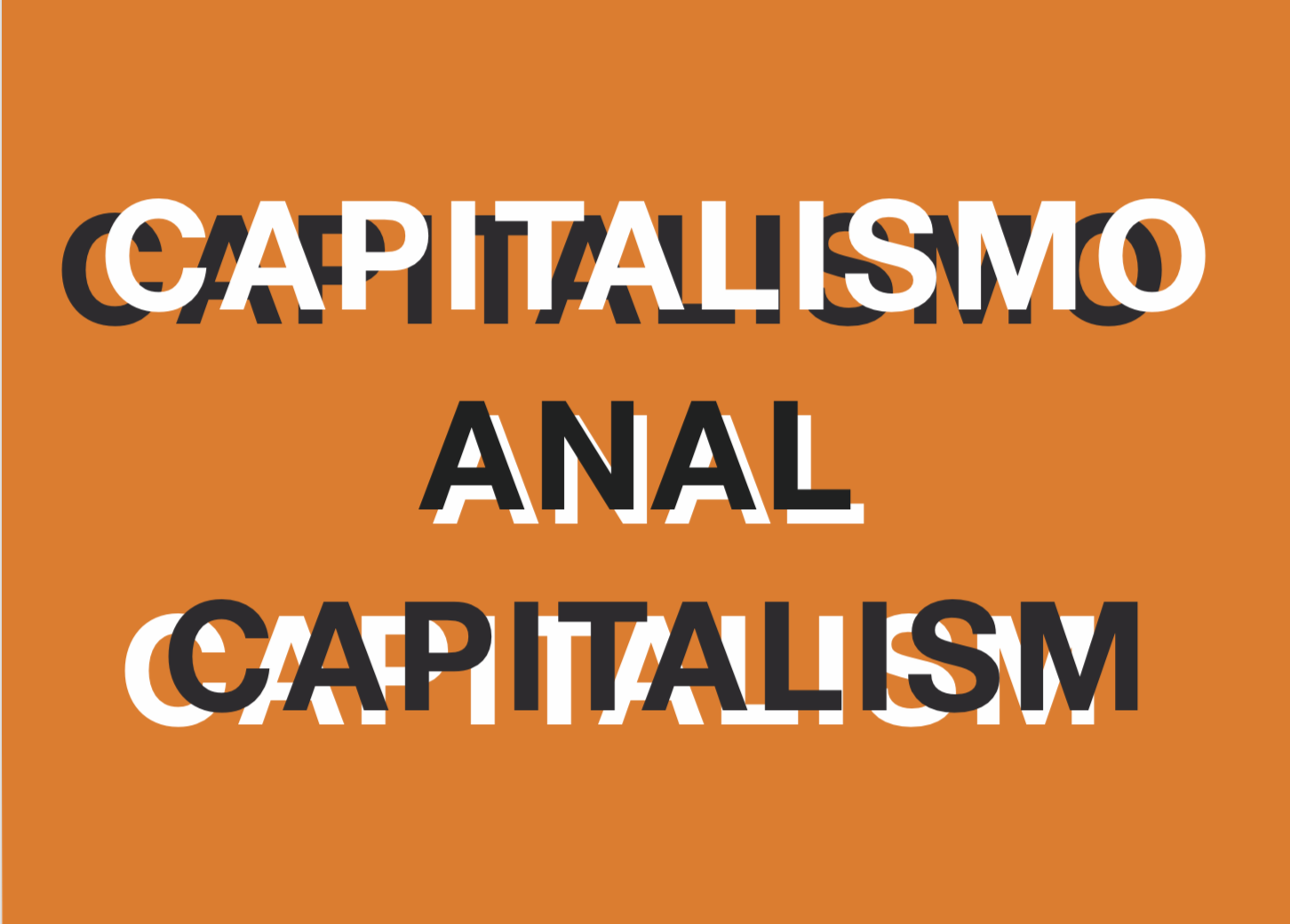

Exhibition poster.

Facade detail.

Facade detail.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

Exhibition view.

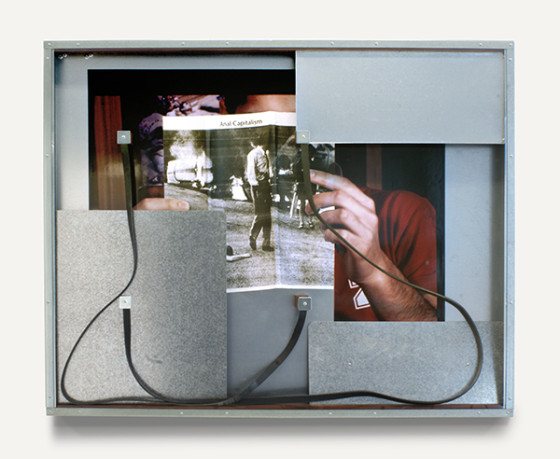

Capitalismo Anal. 2013. 110,5 x 136,5 x 8 cm. Photographs, Wood and rubber in galvanized steel case.

Capitalismo Anal (Detail). 2013. 110,5 x 136,5 x 8 cm. Photographs, Wood and rubber in galvanized steel case.

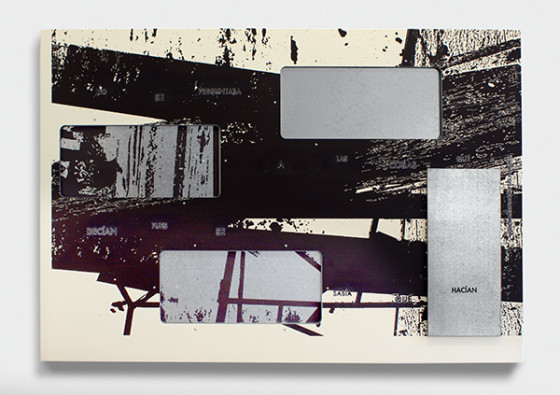

Capitalismo Anal 1. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

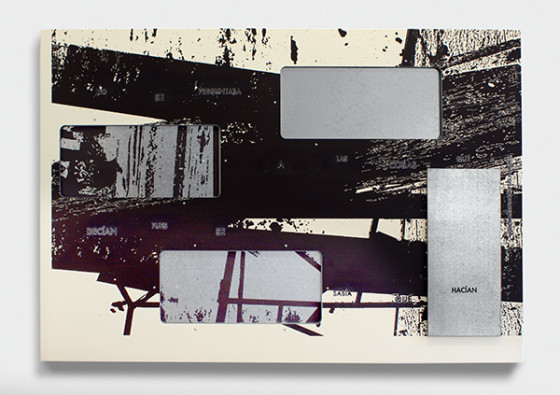

Capitalismo Anal 2. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Capitalismo Anal 2. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Capitalismo Anal 3. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Capitalismo Anal 4. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Capitalismo Anal 5. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Capitalismo Anal 5. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Capitalismo Anal 6. 2013. 120 x 177 x 6 cm. Construction in painted and printed galvanized steel sheet.

Les Limites. 2013. 130,5 x 120 x 8 cm. Imágenes fotográficas, madera y goma en caja de acero galvanizado.

GENTS. 2013. 110 x 135 x 8 cm. Photographs, Wood and rubber in galvanized steel case.

No hay Identidad. 2011. 152,5 x 204 cm. Images and photographies collage.

Entelequia. 2009 - 2013. 321 x 400 x 87 cm. painted and printed metal panels, sound recordings.

Entelequia. 2009 - 2013. 321 x 400 x 87 cm. painted and printed metal panels, sound recordings.

Information

Txomin Badiola’s work became known in the mid-1980s, in the context of what was conventionally called “New Basque Sculpture”, which brought together a group of artists based in Bilbao. This group was characterized, firstly, by its claim of a specific vision of formalism as an aesthetic position with a potentiality for cultural critique at the time of the surge of Trans-Avantgarde and Neo-Expresionisms; and secondly, by its resistance to dominant discourses, developing a practice and a discourse that denied the mutual exclusivity between modern and postmodern lexicons. In the case of Badiola, this position led him, at the end of the decade, to a deconstructive attitude, whose first goal was to address issues related to the critical reception of his previous work, being its utmost materialization the exhibition Who’s Afraid of art?, held in London (1989) and in Madrid (1990). During the 1990s, Badiola’s works evolved into a certain type of hybrid devices (or as he calls them bastards) typically conformed by a sort of architectural element confronted to a plurality of sign-systems. Badiola made use of what he calls, after Lyotard, “Bad Form”: a form being simultaneously the law and its transgression; a precarious and unstable form where desire remains trapped. In fact these works constituted a mise en scène of desire as constructor as well as destructor of realities, expressing a specific notion of the political: “…first, as semiotic excess, then deconstructing it before finally (re)articulating it by forcing it to a blaspheme, by promiscuity, contiguity among politically codified referents and others which taken from conventional political logic would be innocuous. His aesthetic discourse works on two levels: it deconstructs politics by means of the parodic saturation of its traditional referents and at the same time establishes the conditions of possibility for culturally, symbolically and reflectively articulating politics as an other.“1 Many of these works were assembled in the retrospective exhibitions held in 2003 at the MACBA, in Barcelona, the Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao – as a matter of fact entitled Bad Forms –, and in 2007, La Forme qui Pense, at the Museum Saint-Etienne Metropole, France.

During the last decade, Badiola has developed a personal activity regarding the notion of “inheritance” which differs from postmodern appropriation or citation; a peculiar affective mode of historicity, where again desire is fundamental: “The subject-artist is a surface on which, like on a blank page, signs, words, stimuli settle down. Where Badiola says “desire” it could also be read “love”: the artist as a receiver is placed in the position of a lover, and we know that in love the dialectic between giver and receiver is constantly stressed, subject to constant investments and changes of position”2. In such an approach, Badiola uses systematically “misinterpretation” as a useful tool, abusing, destroying and rebuilding “texts” regardless their provenance: literature, the visual arts, politics or the media. In Badiola’s recent work – as evidenced in the set of exercises he proposed within the project Primer Proforma 2010 –, he pays special attention to the relationship between the inscribed/written language and the spoken one, as a place where it is most obvious the fallacy linking the efficiency of communication to the signified. In these works, his aim was precisely to suspend such linkage; as he states: “… communication should be something appealing not as much to our consciousness as to the plurality we are made of; something that would arise through the act of violating the signifying chains that encloses communication around a meaning that usually responds to one or several orders of representation, i.e., of subjection to the Law.”

In the present exhibition, the piece Entelechy is presented as a large metal billboard. Outwards, it articulates a large space while inwards it is articulated by a multitude of spatial micro-relationships of various kinds, all subjected to its basically flat condition. This work serves also as a screen projecting a spoken text. The audio was the result of one of the exercises in Primer Proforma 2010, which consisted in subjecting two texts to multiple and consecutive translations into several languages until they were totally corrupted with regard to their original meaning. Then, they were read (embodied) by the participants in the exercise, and, by becoming “voice”, those absurd texts regained, in a strange way, a flare of sense. The other body of work in the exhibition gathers several pieces under the title Anal Capitalism. The poster/invitation of the exhibition includes a text on the back – a collection of voices of several authors – regarding the strange brotherhood between capitalism, religion and the excremental in today’s culture; a situation where signifiers traditionally linked to the discourse of emancipation have been abducted, with the consequence of a loss of all value reference. In these works, a series of sentences related to such thematic field have been inscribed on metal constructions with specific material/spatial characteristics. The element of authority normally carried out by any sentence engraved on a surface is, by the same move, affirmed – by its materiality close to a commemorative plaque, a warning signal, or even an epitaph –, and denied – by the manner in which the spatiality of the sentences suspends words in more complex dimensions, offering resistance to the automatisms of reading.

- Martínez de Albéniz, Iñaki. “Blasphemous Contiguities. Txomin Badiola’s Work as a Political Device”. La Forme qui pense/ The Thinking Form. Txomin Badiola 96-06. Saint Etienne: Un, Deux…Quatre. Éditions. 2007, p. 125

Aguirre, Peio. http://peioaguirre.blogspot.com.es/2012_01_01_archive.html